Imagine a time when music came alive through the crackle of vinyl, the whir of cassette tapes, and the gleam of CDs and DVDs.

In the 1990s and 2000s, these classic physical media sources captured hearts and defined an era. Devoted enthusiasts pursued physical copies of their beloved media wherever it was available.

Then the introduction of the iPod and MP3 players, as well as the rise of accessible file-sharing applications began. Napster, a file-sharing application, skyrocketed much to the dismay of musicians who profited off of the gross sales from their discography. This was similar to a thief stealing from store owners, but on a higher count— it was like a burglary on a national scale.

Compress ‘Da Audio, a group, released an MP3 of Metallica’s ‘Until It Sleeps,’ becoming notoriously widespread as the “first pirated music file.”

The namesake of Compress ‘Da Audio is also a biting commentary on the very practices of the music industry. Labels and artists had, for years, been compressing the value of music, reducing it into marketable units (albums, singles) and controlling access to it.

Lars Ulrich was infuriated and in April 2000, Metallica filed a lawsuit against Napster, accusing copyright and racketeering.

Corporations and artists used piracy as a scapegoat, ignoring the fact that the systems they relied on no longer served consumers.

Ultimately, Napster faced ramifications from the Supreme Court and was shut down.

As Napster faded, Limewire stepped into the limelight. Though similar to Napster, Limewire’s decentralized peer-to-peer approach offered users a sense of enhanced security. Limewire filled the void left by its predecessor, Napster, attracting file-sharers seeking a safer alternative. Users could upload and download files with the only risk being occasional malware. These applications are notorious and have been terminated.

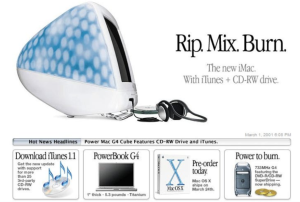

Music-pirating services like Napster and Limewire revolutionized the way people accessed media. These platforms allow users to share and download MP3s, which was a game-changer. Around the same time, Apple also launched their ‘Rip. Mix. Burn.’ 2001 campaign. The process of creating a burned CD was an art form in itself, requiring careful selection of tracks. Software such as Nero or Roxio, allowed users to curate their favorite songs. At times, users would imprint designs via the use of creative programs like Microsoft Paint and Adobe Photoshop. With burned CDs, they could create their own personalized playlists.

President Clinton enacted the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, reinforcing legal streaming. Despite its intentions, the DMCA quickly became seen as a flawed, outdated piece of legislation in the face of the ever-evolving internet. Technological progress reshaped the music industry, altering consumer habits and setting new trends. This shift raised copyright and intellectual property concerns, while also highlighting compensation issues. The evolving landscape continues to challenge traditional notions of music distribution and ownership.

In the modern day, Apple Music, Spotify, and iHeart Radio have continued to grow. Yet, not everyone is satisfied. Artists have criticized Spotify and Apple Music for their low payouts. In contrast, iTunes, with its $0.99 per song price, strikes a better balance. Still, some fans choose physical albums and DVDs to support artists directly. The digital revolution has changed media consumption, but it has also left some casualties and critics.

When faced with either the interruption of ads or the inconvenience of paying for ad-free access, many turn to alternatives instead, seeking raw unedited content.

Consumers are torn between keeping a vast personalized library, or to sacrifice it in vain for monthly subscriptions. The ethical and legal implications of pirating music are hotly debated. Censorship can severely impact artists by limiting their creative freedom and expression. When art is subject to deletion or alteration, it can compromise the integrity of the work and prevent artists from expression.

Record labels play a crucial role in handling promotions, marketing, and artist distribution. Labels possess control over the resources and networks to reach a broad audience through traditional sales and digital platforms. Executives often wield significant influence over an artist’s financial and creative decisions, leading to conflicts over rights and compensation.

SESAC, one of the three major corporations dictating music licensing, has faced criticism in the United States, affecting YouTube due to an ongoing dispute. The US is a viable and susceptible market, so millions of consumers are impacted. The ongoing licensing battles, such as those between SESAC and YouTube, is just a symptom of a wider issue. Its industry is grappling with its inability to evolve with the changing habits of consumers.

The rise of subscription-based services is mainstream, unlikely to diminish. Consumers are split between choosing physical or digital media. If physical media is purchased, customers are satisfied with convenience rather than inconveniences. Additionally, they would not fret if the original content was expurgated, assured they own a copy in essence. However, in the case that they do pursue digital media that is withheld by executives, then extinction is on the table. Preservation is now volatile, left uncertain.

The main point is—who cares? Pirate it. The entire debate over piracy feels like a manufactured crisis at this point. A convenient excuse for corporations and artists to gripe about lost profits while the real issue is much more complicated: media consumption is changing, and no one really seems to be asking if it’s for the better. Piracy wasn’t an epidemic; it was a response to an outdated system.

![JPEGMAFIA & Danny Brown — Scaring The H*es (Video-Game/Album Cover) [CENSORED]](https://www.southlakessentinel.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/SCARING-THE-H0ES-VIDEO-GAME-COVER-1200x802.jpg)