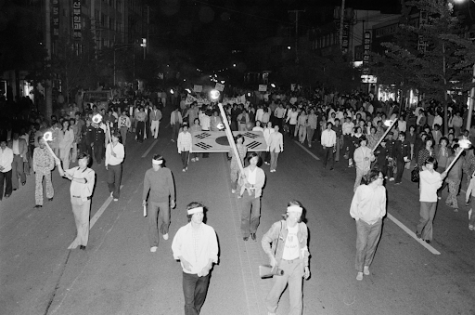

The Gwangju Uprising

Image via The New York Times

South Korea has a complex history dealing with tyrannical rulers and military coups. Starting with Park Chung-hee leading a coup that overthrew the second republic on May 16, 1961.

Park maintained a policy of ‘guided democracy’, with restrictions on personal freedoms, suppression of the press, opposition parties, control over the judicial system, and the universities. He organized and expanded the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA; now the National Intelligence Service), which became a much-feared agent of political terror. The KCIA was known to collect people at night and transport them to detention facilities.

Park was assassinated by one of his close friends and in the aftermath of his assasination Chun Doo-Hwan led a military coup to take control. He kept the majority of Park’s policies and claimed that it was being led by “communist sympathizers and rioters”, possibly acting in support of the North Korean government. There was little to no evidence to support his theory.

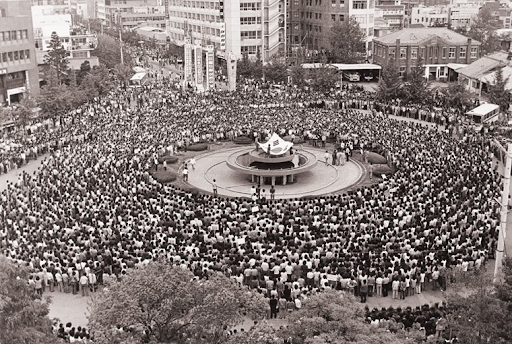

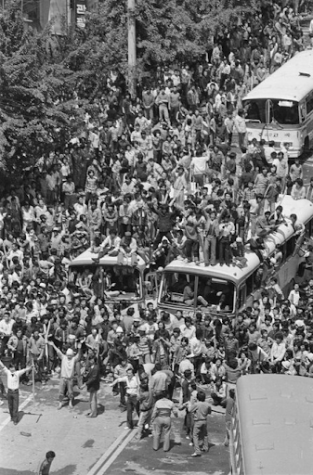

There were a series of protests in Gwangju against military rule that were led by labor activists, students, and opposition leaders, who began calling for democratic elections. Gwangju had a long history of political opposition and had a large outrage toward the Park regime; it was the center of the pro-democracy movement. On May 18, an estimated 600 students gathered at Chonnam National University to protest against the suppression of academic freedom and were beaten by government forces. Civilian protesters joined alongside the students. With the approval of the United States, which had maintained operational control over combined U.S. and Korean forces since the end of the Korean War, Chun’s government sent special paratroopers from the Special Forces to Gwangju to contain the protesters. When the soldiers arrived, they began beating the demonstrators. Rather than put the protest to rest, the brutal tactics had the opposite effect, ending with more citizens joining in.

As the uprising continued, protesters broke into police stations to seize weapons. The protesters armed themselves with bats, knives, pipes, hammers, and whatever else they could find. They faced 18,000 riot police and 3,000 paratroopers. On May 20 a newspaper called the Militants’ Bulletin was published to counter the “official” news being published by government-run media outlets such as the newspaper Chosun Ilbo, which had characterized the protesters as hoodlums with guns. By the early evening of May 21, the government had retreated, and the citizens of Gwangju declared the city liberated from military rule.

The liberation lasted only six days. On the morning of May 27, Chun’s military forces unleashed tanks, armored personnel carriers, and helicopters that began attacking the city. It took the military only two hours to completely crush the uprising. According to official government figures, nearly 200 people, the majority of them civilians, were killed in the rebellion, but Gwangju citizens and students insisted that the number was closer to 2,000. The bodies of the protesters were collected by the government, and either thrown into mass graves or burned.

The Gwangju uprising inspired other democratic movements across the country that eventually led to democratic reforms. The Gwangju Uprising is a symbol of South Koreans’ struggle against authoritarian regimes and their fight for democracy.

Amany Nassar is a Junior at South Lakes and this is her third year writing for the Sentinel. She loves to read in her free time along with playing flag...